Two Toddlers Go Out to Sea

Dated October 25, 1883, an item in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania’s “Weekly Notes of Cases” announces a divorce petition. It was filed by Marcus Heilbron, who wished to leave his wife, Rosa. Marcus states that Rosa “hath offered such indignities to the person of your petitioner as to render his condition intolerable and his life burdensome, and thereby forced him to expend several hundred dollars, as she, the said Rosa, demanded a trip to Europe and was bound to see her parents in Europe and other relatives, and left your petitioner alone at Homestead, in Pennsylvania, and your petitioner was forced to give up his home and break up housekeeping, and thus rendered the condition of your petitioner intolerable and his life miserable and burdensome, and the fact that she remained away and became the scandal and talk of the neighborhood of Homestead, Pennsylvania.”

The unhappy couple were my paternal great grandparents. What isn’t mentioned in Marcus’ petition is that when Rosa fled to Germany, she brought along my grandmother, Rena. I have a copy of the ship’s log of The Aller, documenting their return trip to the US from Germany. Rosa’s age is listed as 37, and little Rena was 2. They arrived in New York on February 23, 1892. The Weekly Notes says that Marcus initiated divorce proceedings on April 11, just six weeks after Rosa and Rena returned home.

Apparently, the time apart didn’t cool the passions on either side. In the petition Marcus goes on to complain that after she came back from Germany, his wife displayed “many outbursts of temper, not confined to bad language and threats, but accompanied by acts of great violence, and are scarcely denied by the respondent herself.” Marcus further states that “She admits that she broke a glass door in his store, and interfered with his customers; that she broke dishes and threw them down the stairs, threw hot coffee on the girl, and on two occasions, when her stepsons complained of the dinner, she brought in slop and threw it on the table.” It certainly appears that my great grandmother had a fiery temper, no doubt provoked by Marcus’ abuse. I’m sure he made it clear to one and all how much he loathed his wife, and wished to leave her, and thus Rena as well.

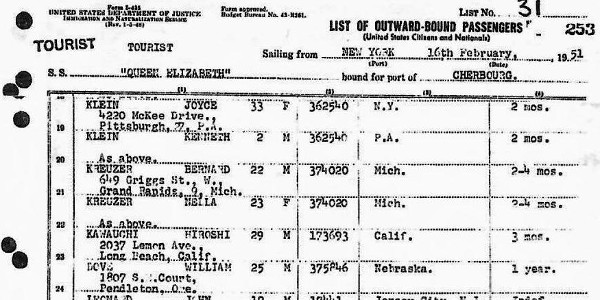

I also have a copy of a ship’s log for a voyage taken almost exactly 59 years after Rosa and Rena returned from Germany. Joyce Klein, age 33, and her son Kenneth, age 2, are listed as traveling in tourist class on the Queen Elizabeth. It sailed from New York on February 16, 1951. My mother was taking me to Germany so we could meet up with my father, who had left home some weeks previously to do research in the laboratory of a German scientist in Berlin. This was less than six years after the conclusion of WWII, in which my father had fought the Germans for five years. My father had lost relatives in the camps on both Rena’s side and his father’s side of the family.

Perhaps even more remarkable than that my father chose to work in Germany so soon after the war was that by going there he left my brother, who had been born just months previously. More amazing still is that my mother too left her infant son; when she and I boarded the Queen Elizabeth, Doug was a mere four months old. Years later, after I became a parent, I asked my father how he could possibly have left Doug at such an early age. He blithely replied, “He was so young, he didn’t know the difference.” And how could my mother do so? “Your mother was very strong-willed. She really wanted to come to Europe while I was there.” And who took care of my brother while the rest of the family were in Europe? “We found a lady from the Salvation Army.”

The recent discoveries of Marcus’s divorce petition and the ships’ logs has created an even deeper bond between me and my grandmother. At the age of two, our mothers took each of us across the ocean to Germany. Both voyages were triggered by our fathers: Rena’s mother was fleeing from her abusive father, while my mother was taking me in tow to reunite with my father. But even though the motives for each trip were different, Rena and I both must have felt apprehension, confusion, and fear.

My grandmother was no doubt a front-row witness to the tense and violent relationship between her parents. From the divorce petition we know only Marcus’ side. But family lore has it that he deserved everything my great-grandmother served him—broken dishes, slop, and all. And though my mother was taking me to–not away from–my father, I must have been very aware that my baby brother had been left behind. He was abandoned first by my father, and now by my mother. Though she chose to take me along this time, what guarantee was there that it wouldn’t be Kenny who would be left with the Salvation Army lady on the next trip?

So as my grandmother walked the decks of The Aller in 1892, and I walked the decks of the Queen Elizabeth 59 years later, I doubt that we were carefree children enjoying our ocean voyages. More likely, we were each anxious about the family dynamics, and worried about what we would find on our return home.

I don’t remember being consciously aware of my parents’ abandonment of my brother. And I wouldn’t be surprised that after the divorce my grandmother repressed her awareness of her parents’ mutually abusive behavior. But she couldn’t ignore her father’s absence; after the divorce he left, and cut all communication with his family.

When she was about ten, in an act of tremendous courage my grandmother found out where Marcus was living and went to his house. He refused to talk to her, or even acknowledge her presence. Thus, repressed or not, her early childhood memories of rejection were resurrected and reinforced. And when, just before I turned fifteen, my mother died of cancer, her death reverberated as the ultimate abandonment of not only my brother, but of me.