The Queen Mary

About four years ago I went to Long Beach, CA to give a talk. But of more interest to me than the conference was that Long Beach was home to the Queen Mary. After taking passengers across the Atlantic for 31 years, this ocean liner was permanently docked at Long Beach and converted into a floating hotel. I was drawn to the Queen Mary because, when I was two years old, my mother took me to Europe aboard this ship. The purpose of the voyage was to rendezvous with my father, who had gone to Berlin to work in the lab of a famous German scientist. I wrote about this trip in a recent blog post.

I vividly remember standing on the deck in mid-ocean, looking up at one of the huge smokestacks. It suddenly belched black smoke and emitted a terrifying, bone-shaking blast. Well, I say I vividly remember this experience, but in fact I probably don’t. Psychologists believe that kids rarely retain memories from such an early age. It’s more likely that my memory was induced by several iconic photographs my mother took on the ship, as well as stories she told me over the years. But real or induced, I’ve held that image of standing at the base of the belching, blasting smokestack for almost 70 years. So being in Long Beach was an irresistible opportunity to retrace my footsteps on the venerable decks of this famous ocean liner, to which I had a special relationship.

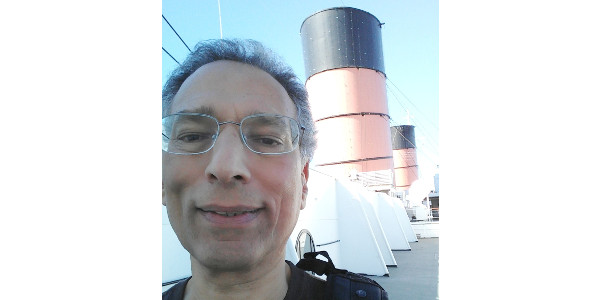

Since I’d arrived the day before the conference began, there was plenty of time. A long waterfront walk from my hotel took me to the Queen Mary. Signs led me to an outdoor elevator that went up several stories to the main deck. As soon as I stepped onto the ship, I saw them: three enormous orange and black smokestacks (which I soon learned were actually called “funnels”) looming above me. An unexpected shiver ran through my body. Walking to the base of the middle funnel, I looked up at its immense height. For a two-year-old, it must have seemed even taller! Was I standing in this exact spot when it smoked and hooted so many years ago?

I strolled all along the deck, touching and then standing beneath each of the other two funnels to be sure I had the right one. I took many selfies. And, very uncharacteristically, I approached another tourist and asked him to take some photos with my phone. Not only that, I also realized I needed to share how momentous this occasion was, so I told him about being on this ship as a small child, clearly long before he was even born. He smiled indulgently.

Then, for the next several hours I walked up and down the many levels of the ship. At some point, I figured, I’d pass the cabin where my mother and I stayed during our Atlantic crossing. I think I was hoping for a sort of dowsing-rod effect, so that I’d experience a special tingling when I came upon the door to that very cabin. But though I felt no particular prickles after my extended promenade, it was deeply moving to be on the same ship, walk the same decks, and see the same funnels that I had so long ago. As I almost compulsively touched the many railings, doorknobs, and furniture all over the ship, I felt transported back to that time. Memories–or perhaps, pseudo-memories– welled up. No matter which, I felt much more connected to my long-gone mother than I normally did, and to our time together on that voyage. My talk at the conference the next day went fine.

Recently I joined an ancestry website that offered links to all sort of historical data. As a result, I’ve been digging into my past. Naturally, one of the things I was particularly eager to find was concrete evidence of my European trip as a toddler. After considerable searching, I found it: a ship’s log documenting that Joyce Klein, age 33 and Kenneth Klein, age 2, departed New York City for Cherbourg on 16 February 1951. But wait–the ship was The Queen Elizabeth! How could that be, since I distinctly recalled that we had travelled on the Queen Mary? Then it occurred to me that maybe we went out on the Queen Elizabeth, and returned on the Queen Mary. After all, my “memory” of the voyage consisted of a single image beneath a huge orange and black funnel–the memory must have been from the homeward journey. I searched further. Bingo! I found the ship’s log for the return voyage: Joyce Klein, 34 (her birthday occurred during our time abroad), and Kenneth Klein, 2, left Southampton for New York on 29 March 1951. And the ship? Inexplicably, it was again the Queen Elizabeth! I was stunned.

Almost in a panic, I Googled these two ocean liners. It turned out they were sister ships, both constructed in Scotland for the Cunard Line. The Queen Mary was built first, beginning trans-Atlantic sailings in 1936. The Queen Elizabeth was completed two years later. It was closely modeled after the Queen Mary, but with an improved design that utilized just 12 boilers, rather than the Queen Mary’s 24, and only two funnels, to the Queen Mary’s three. Comparing photographs online, the funnels looked quite similar—huge, orange and black, and slightly tilted toward the stern of the ship.

I “knew” that we had sailed on the Queen Mary, but undeniably our trips were both on its sister ship. Had my mother mistakenly told me the Queen Mary? I highly doubt it. Apparently, at some point during the intervening decades—possibly even just before I went to Long Beach—the Queen Elizabeth had somehow morphed into the Queen Mary.

The Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mary indeed looked similar. Thus it’s not surprising that my quite possibly bogus funnel memory was reinforced by seeing the Queen Mary’s funnels. But the fact remains that those weren’t the right funnels, the right decks, or the right railings that had all moved me so much. In retrospect, I felt foolish for having taken all those selfies with funnels I’d never been beneath. And breathlessly telling the fellow tourist that I took a trans-Atlantic voyage on a ship that I’d never even seen before.

This was a case of doubly mistaken recollections: First, I almost certainly didn’t have a real memory of being under the funnel of the ship that took me across the Atlantic. It was most likely implanted by photographs and family lore. Second, I associated the counterfeit memory with the wrong ship. If I’d remembered that our voyage was actually aboard the Queen Elizabeth, it’s unlikely that I would have bothered to visit the Queen Mary at all. I could have spent my free afternoon in Long Beach taking a long walk, or catching up on my reading rather than ambling around a random ship.

A question lingers: since I had no connection with that ship, where did my powerful feelings aboard the Queen Mary come from? Why did I feel so moved? I don’t know. Perhaps it’s simply that when vivid “memories”–accurate or faulty–are triggered, they activate circuits in our brain that powerfully connect us with our past. This helps us gain access to latent emotions. The veracity of the trigger certainly has little to do with the validity of the feelings it gives rise to. I emotionally resonated with something important in my life, even though the feelings had been switched on by a case of mistaken identity. Such an intense response seems just as genuine, and just as significant, as those arising from “true” memories. The main downside seems to be a little collateral embarrassment when the mistake comes to light.

I haven’t deleted the many photographs of me standing beneath the Queen Mary’s funnels, nor do I plan to do so.