Uniform Authority

The official gave me a pen from the “clean pens” container, which sat right next to the one labelled “used pens.” Then he took a clipboard that had just been handed to him by another patron, slapped a form on it, and offered it to me. That got my back up. “Excuse me,” I said, less gently than I’d intended, “why do you sanitize the pens, but give me a clipboard that was just touched by someone else?” He looked surprised and said, “They’re different.” “Really?” I said, “Why would a pen be a fomite, but not a clipboard? If anything, the clipboard has more surface area for virus transmission.” “I don’t want to go there!” he said defensively, “but if you insist…” he roughly rubbed down the clipboard with a sanitizing wipe, put the form back on it, and shoved it my way.

Since I do a lot of covid testing, I was recently classified as “1A,” and invited to receive the Moderna vaccine. That’s why I was checking in at my local vaccination center. The man at the desk had a fancy ID badge and wore a bright vest that said Community Emergency Response Team, or something like that. He looked very official. And yet, he didn’t seem to understand basic principles of virus transmission. Still, he seemed offended that I had the temerity to challenge him. I wonder if he was actually trained for his function, beyond how to hand out and collect the forms. Perhaps unfairly, I decided that he probably didn’t even know what a “fomite” was.

The authority and competence conferred by a uniform is striking. Even if they weren’t carrying a gun, most of us wouldn’t think of disobeying–or even questioning–a person wearing a police officer’s uniform. TSA officials, fire fighters, security guards, and even flight attendants gain automatic credibility because of what they’re wearing.

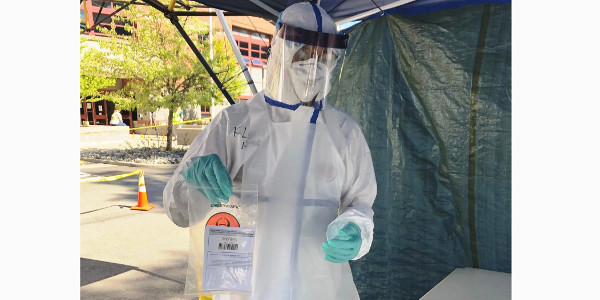

The sense of authority is not only experienced by “the public,” but redounds to the uniform wearers themselves. I certainly feel it when I do covid testing. How could I look any more authoritative than when I’m swathed in PPE—gown, gloves, N95 mask, and face shield? (see photo). When I motion a driver to maneuver her car to my spot in the testing area, I expect her to promptly comply. When I tell a passenger to roll down his window, I feel fully entitled to ask him all sorts of questions before administering the test. And then for him to happily let me poke a long swab up his nose. If I told him to, he’d probably get out of his car, stand on his head, and yodel. I have to say, enclosed in my elaborate PPE uniform, more than once I’ve been tempted to give a definitive answer to a question without actually being sure I was right.

And, of course, when I’m wearing a white coat and have a stethoscope around my neck, a complete stranger will readily disrobe at my request. It’s not simply that the encounter occurs in a hospital or a medical office. Imagine how a patient would react if the receptionist or a member of the cleaning crew came into the exam room and told the patient they were going to do a rectal exam. No, it’s the uniform, not the location, that matters.

One time when my resident was busy with an emergency, I was called to start a subclavian IV line. In my scrubs and white coat, I introduced myself to the patient and told him what I was about to do: anesthetize the skin halfway between the shoulder and the neck, then insert a large-bore needle just below the collar bone. Then I’d thread a long IV tube through the needle until its tip sat just above the entrance to the heart. He shrugged and said, “Fine, doctor.” With my hand slightly shaking, just before starting the procedure I said, “Oh, by the way, I’ve never done this before.” He laughed at my joke, and we both felt more relaxed. Everything went fine. I can’t recall if I ever told him that I had actually been telling the truth.

After a short wait, the official at the check-in desk motioned me to go to one of the vaccine stations. The vaccinator was wearing a fancy vest and a Medical Reserve Corps badge. She looked very official, and thus very competent. I noticed that after her name on the badge it said, MD. Hmm. “Hi,” I said, “I’m a doctor too. I think the last time I gave a shot was in medical school. How about you?” “Well,” she said, with a faint smile, “that’s pretty much true for me as well. A nurse gave me a little refresher course this morning.” “So am I your first patient?” I asked. “No. You’re about the ninth” The shot was OK, but certainly not as slick as if a nurse had given it.

Since like my vaccinator I’m part of the Medical Reserve Corps, I may be called up to start giving vaccinations when Phase 1B kicks in and the number of people needing shots dramatically increases. If so, I’ll certainly look at some YouTube videos, and get instruction from my wife, who, as a nurse has given far more shots than I ever will. When I set up my station, all gussied up in my official vest and MRC badge, I hope the first recipient will assume I know how to give a good shot. I probably won’t volunteer that the last one I gave was almost 50 years ago.

During my break, I’ll have to see if that same official guy is manning the check-in desk. If so, I’ll have to resist the temptation to introduce myself, puff out my vest-swathed and badge-decorated chest, and explain to him what a fomite is.