Circle M Youth Ranch

As a kid, I was sent to some unexpected summer camps. None were regular Jewish camps, which would have seemed the natural destination for this child of a suburban Jewish family. For several years I went to a YMCA camp on the Chesapeake Bay called Camp Letts. The camp motto was “Let’s Camp!” Maybe that snappy slogan made it irresistible to my parents.

But the camp that made the biggest impression on me was the Circle M Youth Ranch, in Capon Bridge, West Virginia. My brother and I were sent there for two summers, when I was about 12 and 13. Unlike Camp Letts, the Circle M didn’t have a motto. But it did have a camp song. Unaccountably, this song has been an intermittent earworm for over half a century. It was sung to the tune of I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl That Married Dear Old Dad. Of interest, I Want a Girl was composed by Harry Von Tilzer in 1911. It turns out that Harry was born in Detroit in 1872, and his birth name was Aaron Gumbinsky. His parents were Polish Jewish immigrants. Maybe this Jewish connection is what drew my parents to send me to the Circle M. Anyway, the song went like this:

I want to go to Circle M

just to have some fun.

It is the camp, and the only camp

where I can have some fun.

A good old southern camp with colonel there;

horses, ponies, and cows need care.

I want to go to Circle M

just to have some fun.

Well, I did indeed have some fun. But I never understood why it was the only camp where that was possible; Camp Letts was fun too. Or at least so I thought at the time.

And what about the colonel there? Well, there actually was one—he ran the place, and was revered by one and all. His obituary is on the McGuinness Funeral Home website: Col George E “Smokey” Stover, USAF retired, passed away at age 87 on February 15, 2006. The Colonel was born in Winner, South Dakota and raised in Wyoming and Nebraska. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was a highly decorated WWII veteran. Among other things, he served on the staff of the Supreme Allied Commander General Eisenhower. After the war, while serving his country in Hawaii, he established a scout camp, which was named in his honor. Because of his distinguished service to scouting, he was presented with the Silver Beaver Award.

The obituary went on: “He retired from the Air Force in 1961 and established a youth summer camp and operated a 4,000-acre farm in Capon Bridge, West Virginia.” There it was! The obit concluded by observing that Col Stover was “an outstanding citizen, husband, father, grandfather, and friend; and one of the reasons they call it the ‘Greatest Generation.’ ”

I do remember the commanding presence of The Colonel at the Circle M, but I don’t remember the cows that needed care. On the other hand, I certainly recall all the horses and ponies–this nerdy Jewish kid from the suburbs learned to ride them. And even to single-handedly put on a saddle, bridle, and bit. Soon, I was actually competing in rodeo events—my favorite was the cloverleaf barrel race. At the final rodeo, I came in third. That earned me a white ribbon, which I proudly displayed on my bedroom wall for many years. Never mind that there were only five competitors in my age group.

My brother, though two years younger, was a very good rider. But he hadn’t quite got the hang of how to put on a saddle. The trick was to knee the horse in the ribs to make it exhale, then quickly tighten the girth. This prevented it from puffing out its chest in an attempt to keep the saddle cinched comfortably loose. One time Doug mounted after putting on his saddle. Then he dubiously yelled to the instructor, “Hey, Dave, I think this thing is a little loose!” He demonstrated the truth of his observation by rocking from side to side. On his third sway to the left, perhaps while his mount was in the middle of an exhalation, the saddle rotated around the horse, and ended up under its belly. But my tenacious brother hung on, and came to rest suspended upside down, framed by the horse’s four legs. I howled—the Circle M was indeed a great place “just to have some fun”! Even if it was at my brother’s expense.

The other memorable Circle M activity was skeet shooting. I don’t think I’d ever touched a gun in my life, other than one time gingerly stroking the grip of my father’s service revolver left over from World War II. But here I was, this kid on the verge of starting to study for his bar mitzvah, in Capon Bridge, West Virginia, learning how to handle a 16-gauge double-barrel shotgun. We shot at circular ceramic targets called “clay pigeons.” After carefully planting my feet and snugging the shotgun tight against my shoulder, in my most manly voice I’d yell “pull!” This was the signal for the counselor controlling the machine, called a “trap,” to activate it, flinging a clay pigeon high into the air. I followed its trajectory through my gunsite, and at the theoretically optimal moment pulled the trigger. On several occasions I actually scored; how utterly satisfying it was to see that terra cotta flying saucer shatter in midair! Sometimes, when the trap wasn’t working, we simply shot at coke bottles the instructors flung into the air. Amazingly, I don’t remember anyone ever getting hit by flying fragments.

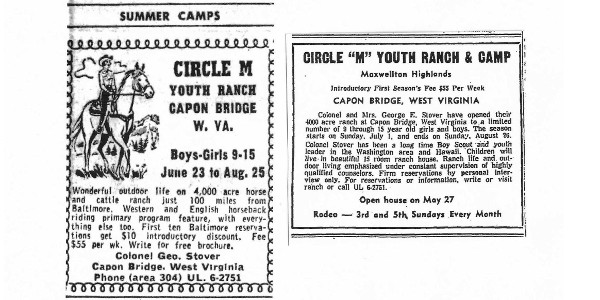

Hoping to activate more memories–or correct the ones I had–I did some extensive Googling of “Circle M Youth Ranch.” There wasn’t much to show for my efforts: I gleaned two ads from 1963 (both featured at the top of this post), and a single article. It was from the June 4, 1966 issue of the Weirton Daily Times, Weirton, West Virginia. The story began, “Youngsters with a taste for the ‘wide open spaces’ and an urge to get away from home this summer can conjure up imaginations of the wild west on the Circle M Youth Ranch in eastern West Virginia.” So, apparently my brother and I—or perhaps more likely, our parents–had a taste for the wide-open spaces, and a wish to conjure up imaginations of the wild west. And it was almost certainly our parents, not us, who had an urge for us to get away from home for the summer. The article went on to state that “Recreation includes” swimming, canoe trips, boating, mountain climbing, archery, horseback riding, and “rifle and shotgun target shooting under National Rifle Association standards.” Yikes–who knew that in my youth I was taught how to shoot a gun by the NRA!

As long as I was already Googling, it occurred to me to see if the colonel’s son was still around—the obituary notice said that Colonel Stover passed away at the home of his son, James, of Ruidoso, NM. He immediately popped up on LinkedIn. I learned that “Jim” is the Director of Emergency Services at Lincoln County Medical Center in Ruidoso. And not only was he too in the medical field, but it appeared that Jim and I were was almost exactly the same age! So he was undoubtedly at the Circle M when I was–maybe it was Jim who won the blue ribbon in the cloverleaf barrel race when I got the white. So I wrote him a warm, maybe even a little gushy, message to his LinkedIn account telling him who I was and saying that I’d love to learn more about his growing up on the Circle M Youth Ranch. I was excited about embarking on an extended correspondence; perhaps he even remembered me as an especially unusual camper. But alas, I never heard back.

I did one final round of Googling. The only new thing that came up was a tiny entry on the website of the Secretary of State of West Virginia: On April 20 1967 “Circle M Youth Ranch and Camp, Inc. was dissolved by court order.” It didn’t say why.

So I’m left with fond memories of a corny camp song, skeet shooting, and cloverleaf barrel racing. I wonder what else went on at the camp that I don’t remember. But my only potential link with the Circle M didn’t respond to my note. I wonder why it was dissolved by the court. But the website didn’t say. And I wonder why my parents sent me and my brother there in the first place. Did they just randomly come across one of those tempting ads in the newspaper and think, why not? Did they learn about it from friends who gave a glowing recommendation after sending their kid there?

Or maybe there was a deeper reason why they sent me first to Camp Letts, and then to the utterly goyish Circle M. Even though they were raised in very Jewish parts of Brooklyn and Pittsburgh, when they were growing up in the 1930s anti-Semitism was rampant. Maybe they, the children of immigrants, wanted to embed my brother and me in the wider American culture, giving us the chance to experience things that were not available to them. Like going to a YMCA camp, and to a good old Southern camp with colonel there. Where we could do very non-Jewish things like ride in rodeos and learn to shoot guns. I’ll never know. But whether I ended up at the Circle M simply by chance or by careful parental calculation, I value the experiences I had there, which were unlike anything else I experienced growing up. Maybe that’s why that song has stuck in my head all these years.