Hearing is believing. Or is it?

As a badge of my membership in The Presbycusis Club, I was recently fitted with hearing aids. Being a typical aging male, I’d had increasing difficulty understanding my 6-year old grandson, which was quite distressing. On walks, I often couldn’t hear the birdsong that delighted Annie. And in restaurants I tended to tuck my chin and focus on my food, since it was often hard to hear what anyone was saying. In other words, the usual stuff of geriatric hearing loss.

The snazzy Bluetooth hearing aids have been transformative. I can hear Ari loud and clear. The birds sing again. And I can talk and listen at Bruciato’s while munching my margherita.

But in the early days of the aids a new and unpleasant auditory world revealed itself: There was a sudden symphony of snap, crackle, and pop whenever I flipped the pages of a magazine. The jangling of my keys was painfully sharp. And driving was a nightmare–the oppressive sound of wind whooshed through the car even when the windows were closed, the tires produced an invasive high-intensity hum, and unidentified intrusive noises were everywhere.

Had I’d been missing these sounds for years? And if so, why did I want them back? “You’re experiencing sensory overload,” my audiologist helpfully explained. So she dialed down the volume of the high frequency range, which is of course where most geriatric hearing loss occurs. This moderation indeed made things more tolerable, and was a reasonable compromise between being aid-less and over-aided. During the succeeding months she gradually ramped up the high frequency sensitivity, which became increasingly tolerable, and improved my hearing.

This ability to manipulate what’s pumped into my ears raises a question: Is what I’m hearing “natural?” That is, with my hearing aids installed are the sounds I now perceive the same as when I was a young pup with pristine cochlea? Or has my current sound palate been artificially colored to optimize my hearing? And how does what I hear now compare with what Annie hears? And Ari? And, for that matter, what my grand-dog hears? Or a bat? As we all know, many animals perceive frequencies that are far above the range of even perfect human hearing. Nevertheless, though we can’t perceive them, such high frequency “sounds” are considered real.

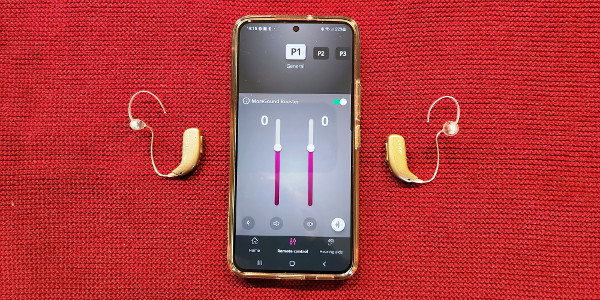

While exploring the options on my hearing aid app (yup, it’s true–there’s an app for everything!), I came across a toggle labelled “MoreSound Booster.” More sound, or even “MoreSound” seemed like a good thing—I asked the audiologist what it was about. She said it boosted voices and muted background noise so it was easier to hear people talking. “Well that seems like a no brainer,” I said, “so why not have it on all the time?” She said it’s only for when I’m tired, or are having a lot of difficulty hearing someone. Otherwise it should be off “because it’s not natural.” Hmm. Why should I care about having unnatural hearing if it allows me to hear better? X-ray vision isn’t natural either, but it might be nice to have in certain circumstances.

Recently someone asked my good buddy Steve, an astrophysicist, if those stunning photographs from the Webb telescope were “real”. By which she meant if that’s what would be seen simply by looking at the unaltered images collected by the telescope. Steve said no—the wavelengths of all the images are in the infrared. Thus we would see absolutely nothing unless they were digitally transformed into wavelengths that the human eye is capable of perceiving. In that sense the beautiful images are not natural, but “artificial” since what we are seeing is visible only by virtue of manipulation. But they certainly represent real objects that reside in the universe. Similarly, the sound palate delivered to me by my Oticons is probably not exactly what I would have heard in my youth. But they get the job done.

And then, of course, there’s augmented reality. Ultimately, is there much difference between augmenting my hearing with hearing aids and augmenting reality by adding additional layers of perception? I actually know very little about augmented reality. Apparently, certain goggles can superimpose information on what’s being seen, for example the name of the mountain you’re looking at, or the menu of a restaurant you’re walking by. I suppose that my hearing aids could do the same in the aural realm. Maybe the app could be programmed to insert appropriate sounds into the ambient environment. For example, native birdsong appropriate to the neighborhood through which I’m walking. Or local color music. Or maybe even a commentary on a historical event that occurred in the building I’m walking past. Who knows, this probably isn’t fantasy—I wouldn’t be surprised if a company somewhere is developing, if not already marketing, something like that. Yikes!

Like a gateway drug, I fear that my innocent hearing aids could be leading me down a path of increasing distance from reality. But for the moment, I’ll take that risk–I love being able to talk to Ari in a crowded restaurant, and to hear the birds sing when I hike with Annie in the woods around Gazzam Lake. Whether or not what I’m hearing is “natural.”