Doctors don’t give shots

Just after I gave her the vaccination, the woman beamed and said, “Thanks so much, that was a great shot!”

“Not bad for a doctor, eh?” I replied modestly.

She laughed. “Doctor, I have to tell you something. When I was sent to your table and saw that you were a man, my heart sank. I prayed that you were a nurse, and not a doctor.” We both cracked up.

“I understand,” I said. “Doctors don’t give shots.”

It’s indeed true. I gave maybe two or three shots in medical school, and after that no more for over four decades. Until a few months ago. Then the Bainbridge Island Medical Reserve Corps asked for volunteers to give covid vaccinations.

Fortunately, my wife, Annie is a nurse. So she gave me some great pointers (get it?). She even had me practice on a poor, hapless orange. Next I watched about a dozen YouTube videos of nurses teaching how to give a shot. Curiously, every one was different; in fact, there was a lot of mutually exclusive advice. Some instructors insisted that it was vital to pull back the plunger before pushing it in; others said that was completely unnecessary. Several said you had to pinch the muscle and skin up in a tent before injection, another said to flatten the skin by pushing down and out with the fingers. One claimed that making a Z-track was essential; two others said Z-track injections were a waste of time. Do a slow, steady controlled insertion. Pop the needle in like a dart. And on and on. I concluded that no matter how I chose to vaccinate, I’d be doing it wrong.

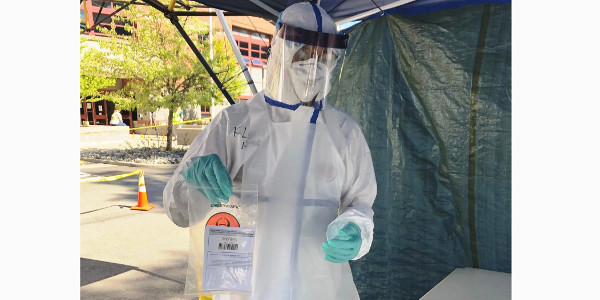

As I drove to the Bainbridge Island Senior Center for my first shift, my stomach was in a big knot. I thought how easy all the Covid testing I’d been doing for the last few months was—after a few swabs, I felt completely comfortable with my technique, and could focus on connecting with the person I was testing. But giving shots was a new skill; I was once again an extreme non-expert. I fantasized ahead to the time when I felt as comfortable giving an injection as I did with nasal swabbing, and so many other medical procedures I’d ultimately mastered.

There’s an old saying in surgical training programs: “See one, do one, teach one.” But in the vaccination clinic this sequence was attenuated even further: The first step was entirely skipped, and I was assigned a station, given a few instructions for how to draw up the Moderna vaccine, and left alone to vaccinate. (I’d already gone over the package insert in detail, so I was quite comfortable with how to handle the vaccine.) I approached one of the other two vaccinators (a nurse, of course), introduced myself, and asked that she watch me to be sure I was giving a proper shot. Fortunately my first victim was relaxed, which helped me relax. I cleansed the deltoid with an alcohol swab, gently pinched the muscle and skin, darted the needle, and injected without withdrawing. No one yelled, jumped, or even sucked in their breath. I asked my patient how it went; she simply said, “fine, I hardly felt it.” My fellow vaccinator went silently back to her own station, and I proceeded to uneventfully give shots to thirty or so people.

Other than the small minority who looked right at the needle and talked on during the vaccination, most people tensed up in anticipation. So I started telling everyone that I’d warn them just before I gave the shot; “I don’t believe in sneak attacks,” I said. Almost everyone seemed to appreciate that. But a few demurred, saying something like, “No, please don’t warn me. I want to be surprised–I like sneak attacks.” Like with just about everything else in life, one size doesn’t fit all.

After I introduced myself, the middle-aged woman sat down, started trembling, and teared up. She was clearly in the ‘tensed up’ category. “Please don’t worry,” I told her. “I’ll be as gentle as I can, and I’ll warn you just before I give the injection.” She shook her head and laughed. “I’m not nervous, doctor. I’m just so excited to finally be getting vaccinated!” After I gave her the shot, we celebrated together.

A young man came to my station wearing a sleeveless undershirt, fully revealing his deltoids–a vaccinator’s dream. His arms were covered with tattoos. I absentmindedly asked him if he was squeamish about shots. He brandished his tattoos and said, “Do I look like I mind needles?” I hooted, and apologized for asking such a silly question.

Arms with tattoos were fun to vaccinate since they provided a target. Once time, literally. The man had a bright red bullseye over his right deltoid. I told him it was an irresistible target, but when I did my measurement (three fingerbreadths below the tip of the acromion), it turned out that the tempting bullseye was too low. So I had to settle for one of the outer rings north of the target.

And speaking of tattoos, at a clinic at the Chimacum Grange, I vaccinated a man with “Loise” emblazoned diagonally across a juicy red heart. I found it very touching. I tentatively asked him, “Is Loise still in your life?” “Yup,” he replied and gestured out to the parking lot, “not only is she still in my life, she’s in my car.”

One of the wonderful things about this work was that I wasn’t being paid. And I had no quotas. So there was no time pressure; I felt free to take just as long as I needed. I explained to each person what sorts of side-effects to expect, and how to deal with them. I sensed that some people simply wanted to get the shot over with, and leave. I respected that. Others seemed eager to ask all sorts of questions about the vaccine, their health, and sometimes even to simply tell me about their work or their life.

People talked about their cancer, or kidney transplant, or a family member who was very ill. More than once I learned that a person wasn’t needle-shy because they had diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis, or another condition that required them to inject themselves regularly. Then sometimes we talked about what it was like to live with such a condition. These were brief, but intense, connections.

I was surprised to see Rafael coming to my station. He had done some wonderful gardening work for us a month previously. As I went over the potential side-effects of the injection I noticed that, even with his mask on, he seemed sad. When I asked him if he had any questions, he looked down, then simply said that during the time he was working for us his mother had died of covid. So he was eager to be vaccinated. I told him how sorry I was, and sat with him a little while after giving him his shot.

The environment where the vaccinations took place was quite unusual. It’s of course rare for any sort of medical interaction to take place in a large space—the typical medical consultation takes place in a little exam room with just the doctor and patient, and maybe a nurse or medical assistant. An operating room may have more people present, but they’re just the staff and a single patient, who’s the focus of all the activity. And even in the ER, the space is limited and curtained off.

But the vaccination centers were different. At the high school gym we usually had between 9 and 12 vaccinators per shift, and over 60 volunteers directing traffic, checking credentials, registering, monitoring, entering data, and keeping track of the vaccines. Over a weekend we sometimes vaccinated more than 2,500 people. I think many who came for their vaccination enjoyed getting a shot in such a big beehive of bustle. They were taking part in an event where they and everyone around them was there for a single purpose: to decrease the spread of a virus, and the illness, disability, and sometimes even death that came with it.

It’s hard to think of another situation where so many people are gathered together for precisely the same goal. At sports stadiums, large groups of people share the same space, but they’re rooting for different teams. At a concert it’s superficially all about the music. But the audience has a rather different focus than do the performers or the paid staff. Perhaps the most similar situation I can think of to a vaccination clinic is a religious service. But even there, people attend for varied reasons—the religious leader, the regular member, and the visitor surely have somewhat different motivations and expectations. At the vaccination clinic, on the other hand, we all shared a single, specific aim, no matter whether we were there to get vaccinated or to volunteer in some capacity. It was so good to be sharing in this goal; I think everyone felt it.

Just as this was a unique environment, it was also unusual in that it was such a simple and happy one. Especially for anything that had to do with medicine and health—there were no orders for further testing, shadows seen on the x-ray, referrals to specialists, or grim diagnoses that had to be delivered. Only a birthing center comes close. The gym was filled with yelps of celebration, elbow bumps of gratitude, and lots of selfies. So far I’ve given more than 450 covid shots. This has been one of the most gratifying experiences of my medical career.

(Note: I’ve made a few inconsequential changes to these stories to ensure the anonymity of each person I mention.)