7 Greenough Ave

Back in the day, when I was in college, I started a commune. Well, with some grandiosity, that’s what I called it (this was the ‘60’s). The building I found to commune in was a big, rambling three-story house at 7 Greenough Avenue in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The landlord was Mr. Fogelman. As far as I could tell, he was a classical shyster lawyer, but still a charming guy. I used to have long philosophical discussions with him when he dropped by to collect the rent. As an aspiring doctor, I naturally felt superior to him. “The main difference between lawyers and doctors,” I smugly stated, “is that the essence of the law is confrontation–the lawyer advocates for his client, and works to discredit the opposing party.” Mr. Fogelman grunted. “Whereas in medicine,” I continued, “the doctor is united with the whole medical system in supporting the patient. The only opponent is the illness or injury which everyone is determined to defeat.” He grunted again and said, “Well, there’s actually just as much confrontation and opposition in medicine as in the law. You’ll see.” I’m not sure I ever did see, but perhaps he had a point.

I proposed the idea of a commune to Susan, a friend and classmate. She immediately signed on, and we began recruiting fellow communards with an ad in the local free newspaper. (Extraordinarily, in those days the internet had not yet been invented!) Our first respondent was a guy called Sumner Silverman. I can’t remember what he said in his letter, but we found him intriguing. Rather than coming to Greenough Ave, he suggested that we meet him in his apartment in North Boston. That seemed a bit odd, but we agreed.

Sumner was short and solidly built, with graying hair and a regulation ‘60’s beard. His diction was somehow formal and old-fashioned. He invited us to sit down on a brown velvet sofa in his dark, spacious living room. The walls were hung with Navajo tribal blankets and colorful bedspreads from India. A vague smell of nag champa hung in the air. After a bit of small talk he excused himself and went into his kitchen. He soon emerged carrying an aluminum tray, bowed slightly, and presented the contents: The tray was paved with thin slices of freshly cut blood oranges. He explained that they were drizzled with olive oil and sprinkled with ground white pepper. “These are really good,” he said, “I’m sure you’ll like them. Now shall we take off our clothes and dig in?” Susan looked at me with popping-out eyes. I’m sure mine popped out just as far. I can’t remember just how we wriggled out of that invitation, but no doubt there was a lot of awkward stammering, followed by excuses that made no logical sense. But somehow, we managed to hightail it out of Sumner’s apartment with all our clothes on. I can’t remember if we even tried those orange slices. I wrote Sumner the next day with some sort of lame excuse: though Susan and I liked him very much, we felt that he just wouldn’t be a good fit for 7 Greenough Ave.

After that inauspicious start, we eventually recruited an interesting crew of about eight people. I say “about” because the number of residents fluctuated unpredictably. We were mostly students, but some residents had real jobs, while others just sort of hung around. Barbara was a graduate student in clinical psychology. One summer afternoon, she came limping into the house after taking a walk along the nearby railroad tracks. She had somehow twisted her foot between the track and a tie, and felt a soft crack. An x-ray showed that she had broken a bone which, since I hadn’t yet started medical school, I was unable to name. Her foot was casted. For some weeks after that Barbara hobbled around the house on crutches, sometimes, for some reason, without a shirt. I found this rather odd. But this was the ‘60s. Years later, perhaps inspired by 7 Greenough Ave, she established a women’s collective farm and ranch in New Mexico.

Danny was another psychology grad student. He had recently come back from a long stay at an ashram in India, where he had learned meditation and eastern spirituality under Neem Karoli Baba, known better as Maharaj-ji. Danny had heard about the ashram from another student of Maharaj-ji called Ram Dass. Ram Dass, formerly known as Richard Alpert, had been one of Danny’s psychology professors at Harvard. Alpert and his colleague, Timothy Leary, did experiments involving psychedelics, most notably LSD, and aggressively advocated their use. As a result they were both kicked out of the university. Then Leary began travelling around the country advising everyone to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” Alpert travelled farther afield, going to India to study with Maharaj-ji. There he changed his name to Ram Dass, and brought his guru’s teachings back to the US. Be Here Now, based on what he learned at the ashram, was Ram Dass’ first best seller. Years later, Danny himself wrote a best-seller, Emotional Intelligence.

Another commune-mate was Meredith, a musician and a poet. She was tall, and seemed even taller since she was topped with a generous head of springy brown hair. Her father was a well-known developmental biologist. I had a special affection for Meredith, since she was one of the few people ever to write a poem about me.

Then there was Jon, who, like Susan was a classmate of mine, and Susan’s younger sister, Phyllis, who became my girlfriend. A sweet but somewhat shadowy guy called David lived there too, though I was never quite sure what he did. Andrew, a book designer and artist who I’d known since junior high school, hung around a lot. There were other Greenough groupies as well.

We took turns cooking, and ate our meals together. Sometimes they were quite intense. In the midst of some lively dinner conversation one evening, just as I was bringing a glass of water to my mouth Susan asked what the time was. I reflexively turned my arm to look at my watch, thereby dumping the full contents of the glass onto my lap. Everyone got a good laugh out of that, including me.

In the spring Danny imported a guru from India to give some lectures at Harvard. On his visit to Greenough Ave the guru offered to dispense free mantras, with which we could mediate. When my turn came he sat cross-legged on the pillow at the head of my narrow bed, while I faced him cross-legged at the foot. He intently examined me, or perhaps my aura, and after a bit of meditation solemnly presented me with my mantra. I remember it, and when I very occasionally meditate these days, I still use it. “It is very important,” the guru said, “to never say your mantra out loud, or to share it with anyone.” I treasure it, and have kept that promise.

After my mantra was bestowed, I began meditating for 20 minutes every day. In the balmy Massachusetts summer I would climb out through the third-floor hall window, cushion in hand, to the old rusty fire escape. I sat cross-legged on the fire escape platform, closed my eyes, and silently recited my mantra, over and over. It was sublime. Occasionally some passing kids looked up and noticed me. They would yell to get my attention, but I kept still, eyes closed, focusing on my mantra. One time, out of the corner of my consciousness I heard a kid say, “Hey, he’s not moving. Do you think he’s dead?” Another answered, “I don’t know; let’s find out.” So they began throwing a tennis ball at me. I steadfastly leaned into my mantra, and tried to erase the irritating kids from my awareness. But the repeated flights of the tennis ball were hard to completely ignore. Fortunately, the fire escape’s elaborate ironwork prevented any direct hits, and the kids eventually lost interest. I guess they thought I really might have been dead.

As psychology students, Danny and Barbara were reflective, and “self-aware.” At one point they both began advocating not just mindfulness, but avoidance of a focus on the self. Thus, they took down all the mirrors in the house, telling us that we shouldn’t be looking at ourselves so much— “look inward, not outward,” or something like that (this was the ‘60’s). Ha, I thought, easy for them to say! They were both not only self-aware, but self-confident and very good looking. What about the rest of us, I fretted, who were much less secure, and needed to make sure our hair was combed and that we didn’t have any bits of lettuce between our teeth before we went to class? I was pleased that before too long the mirrors went back up.

One momentous day Ram Dass paid us a visit, or more accurately paid Danny a visit. Recently back from India, he had a long, grayish beard, and was sheathed in white robes. A string of sandalwood beads hung from his neck. He sat on a stool in the kitchen, placidly drinking the tea that Danny had prepared for him. Those of us lucky enough to be home when he arrived clustered expectantly around him. Ram Dass told us a few stories about life in Mahara-ji’s ashram, but mostly talked about how it felt to be back in the United States, particularly how annoying certain things were. What I remember best is his complaint about his white Jaguar, which had apparently been given to him by an acolyte. “It drives really well,” Ram Dass allowed, “but it’s not very reliable. The damn thing is always in the shop.” This somewhat lessened my awe of him. But maybe he was trying to demonstrate that even while living a deeply spiritual life one mustn’t lose sight of the practical side of things.

During our time together at Greenough we did some moderately weird things—this was the 60’s. One Saturday evening, for example, “we had an idea of mine for dinner,” as I put it later. This is what dinner was like: I lined 28 small paper bags with 28 plastic ones and filled each with bite-sized portions of a different food. Thus, one bag contained chunks of avocado, another cookies, and another, oysters. There were bags of carrots, walnuts, cucumbers, dates stuffed with cream cheese, cubes of bread, banana slices, figs, swiss cheese, and eggs, to name a few more. All my housemates were there, and we invited lots of others, including my cousin Carole. Each person got their own bag. Next, we closed the curtains, turned some music on and the lights off. Then the fun began.

Like dust motes in a shaft of sunlight, in the pitch darkness people began randomly circulating around the room. When two came into contact, without saying a word each was to grab a piece of their bag’s contents, then find the mouth of the other person and feed it to them. So, I might suddenly find a prune in my mouth, while I would feel for the mouth of the prune-bearer and feed it a brussels sprout. When a pair had exchanged bites, they separated, and the Brownian motion continued. The result was that at the end of the evening we had each experienced an unpredictable juxtaposition of textures, smells, and tastes. And of course each person’s order of ingestion was quite different. Some found dinner rather horrifying, while others discovered unique and surprisingly tasty combinations. Subsequently, some of these unusual fusions showed up in Greenough Ave meals.

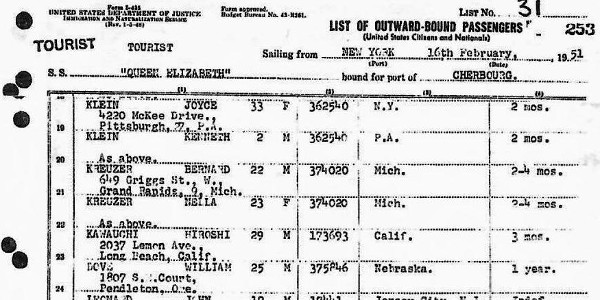

Just a few weeks ago I came across the poem that Meredith had written way back then. That inspired me to track her down. With the magic of the internet, I found her within five minutes. I learned that she had become a published poet and a composer. Her email address popped up too. I wrote her: “Hi, Meredith, this is Ken Klein. As you recall, long ago we lived together with a bunch of other people on Greenough Avenue in Cambridge…” Then, to jog her memory, I mentioned her poem. Here was her response: “Dear Ken, I did live in a group house with Dan Goleman and others in Cambridge—is that what you’re referring to?” Obviously, she had no memory of me, despite my poetic prompt. Deflated, but undeterred I wrote back and reminded her that I had started the commune with Susan. Then I briefly told her about my family and where I was now living. Her reply made it clear that she still didn’t remember me. Nevertheless, she told me about her work teaching children with learning disabilities via Zoom, and that her youngest daughter had gone to art school in Seattle. She concluded, “I have been a certified teacher of Transcendental Meditation technique since 1971—inspired by meeting Dan Goleman so long ago! Thanks for organizing that home, that shifted my life’s trajectory in a wonderful way.” Though she didn’t remember me, I at least had a role in shifting her life’s trajectory. I guess that’s no small thing.